日志

Dylan Yeats 解密1800-1905华人抗争排华法案历史

||

The Chinese Consulate and Chinese Mission, 26 West 9th Street

Chinese Mission at 26 West 9th Street, 1904 Sanborn Map. Image courtesy of NYPL Digital Collections.

1902成了许芹教会包括Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association

3,4层学生宿舍

Around 1885, the Chinese Consulate, which was involved in activist efforts to protect the civil rights of Chinese Americans,

operated out of 26 West 9th Street.

In 1902, the Consulate moved to another office on lower Broadway, and Huie Kin,

a prominent Chinese American missionary, moved his family and his Chinese Mission from 14 University Place into this building.

By this time, 26 West 9th Street also housed the headquarters of the Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association.

The Kin family then turned the third and fourth floors into lodging for Chinese students who were unable to find rooms

elsewhere due to discriminatory renting practices throughout the city.

The building housing the Chinese Consulate was demolished and in 1923 replaced with the apartment building now located on the site.

The Chinese Guild, 23 St. Mark’s Place

The Chinese Guild was founded in 1889 at 23 St. Mark’s Place. Though it was formed in partnership with St. Bartholomew’s Church at Madison Avenue and 44th Street, the Guild served primarily as a secular social welfare and legal advocacy organization for the city’s Chinese American community. Membership cost $2 to join and $1 for every additional year. Guy Maine, formerly a Chinese tea merchant, served as the organization’s superintendent. The Guild included up to 600 members, many of whom worked as laundrymen and faced frequent discrimination in their daily lives.

The Guild organized a choir, Sunday school, and English lessons for its members, as well as assistance with rental negotiations and legal documentation. It also offered support for individuals contacting doctors, lawyers, and police. In 1891, Guy Maine was involved in 217 court cases regarding crimes committed against the Guild’s members, most of which involved assaults-and-batteries and broken laundry windows. “The Master Laundrymen’s Association,” a group of white steam-laundry owners threatened by the competition of Chinese laundries, would launch frequent attacks on businesses owned by Chinese Americans, vandalizing their storefronts. As a result, insurance companies would not cover damage to plate glass used in Chinese American businesses. In a 1901 report, Maine requested that the Guild be made a corporation, giving it the legal right to protect its members. At this time, the building at 23 St. Mark’s Place included a library, music room, dining room, smoking room, gymnasium, and several bedrooms. It was open all day from 9am until 10pm.

By 1898, The Chinese Guild had moved to the 9th floor of the new St. Bartholomew’s Parish House on East 42nd Street. 23 St. Mark’s Place survives today, albeit in highly altered form.

1892年抗议Geary Act 成立公民平等权利联盟( 模仿黑人 公民平等权利联盟)

On September 22, 1892, a group of about 1,000 white U.S. citizens and 200 non-citizen Chinese merchants and laborers gathered at The Cooper Union’s Great Hall to protest the Geary Act. Together, they formed the Chinese Equal Rights League. The Geary Act, which had passed that year, required Chinese residents of the United States to carry a resident permit at all times. If a person did not carry a permit, he or she would risk deportation or a year’s worth of hard labor. Under the Geary Act, non-citizen Chinese residents were also prohibited from bearing witness in court and from receiving bail in habeas corpus proceedings.

At its first meeting, the Chinese Equal Rights League passed a resolution, published as a pamphlet, condemning both the Act’s immigration restrictions and its denial of citizenship to Chinese Americans. The resolution demanded that the act make a formal distinction between recent Chinese immigrants and resident Chinese Americans. The Philadelphia merchant Lee Sam Ping was elected president of the organization. Wong Chin Foo, a journalist and activist who is credited with founding the organization and with coining the term “Chinese American,” was elected as secretary.

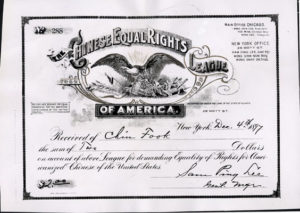

Chinese Equal Rights League Membership Card, 1897. Image courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library.

That year, the Chinese American community raised money to test the constitutionality of the Geary Act in Fong Yue Ting v. United States.

Over the next decade, the Chinese Equal Rights League’s activism extended beyond its resistance to the Geary Act,

focusing on the larger fight for Chinese American civil rights amidst the development of increasingly strict immigration laws.

8888888

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art was founded in 1859 by American industrialist Peter Cooper, who dreamed of educating talented young people at an institution that was “open and free to all.” It was the first in the world to be built with an elevator shaft because Cooper, in 1853, was confident that the elevator would soon be invented. Many public intellectuals have spoken at the Great Hall since, such as Henry James, Mark Twain, William Styron, and Salman Rushdie, as well as seven U.S. presidents including Barack Obama. The striking Italianate brownstone building is also an important site in New York City’s civil rights and social justice history. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and a New York City Landmark in 1965.

On September 22, 1892, a group of 1,000 U.S. citizens and 200 Chinese merchants and laborers gathered at The Cooper Union’s Great Hall to protest the Greary Act, forming the Chinese Equal Rights League. The Greary Act, which had passed that year, required Chinese residents of the United States to carry a resident permit at all times. If a person did not carry a permit, he or she would risk deportation or a year’s worth of hard labor. Under the Greary Act, Chinese residents were also prohibited from bearing witness in court and from receiving bail in habeas corpus proceedings. At its first meeting, the Chinese Equal Rights League passed a resolution, published as a pamphlet, condemning both the Act’s immigration restrictions and its denial of citizenship to Chinese Americans. The resolution demanded that the act make a formal distinction between recent Chinese immigrants and resident Chinese Americans. The Philadelphia merchant Lee Sam Ping was elected president of the organization. Woo Chin Foo, a journalist and activist who is credited with founding the organization and with coining the term “Chinese American,” was elected as secretary. That year, the Chinese American community raised money to test the constitutionality of the Greary Act in Fong Yue-Ting v. United States. Over the next decade, the Chinese Equal Rights League’s activism extended beyond its resistance to the Greary Act, focusing on the larger fight for civil rights for Chinese Americans amidst increasingly strict immigration laws.

More Info:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cooper_Union#Founding_and_early_history